-

The following reflection was sent to us by Augusto Cuginotti as a contribution to our Taking the Revolution Forward collection. After not seeing what he felt was a particularly promising aspect of Brazil’s recent uprisings being represented in the media’s telling of what happened, he decided to contribute his own story about the ‘Dialogue of 1,000 Tables’ that was held in four major cities across the country last June. (Re-printed from www.opendemocracy.net)

Protest alone can’t secure a long-term vision for society, so the straight lines of demonstrations have to be re-shaped into new patterns of participatory democracy and dialogue. This is what is happening in Brazil.

How can the energy of street protests be utilized in the long-term transformation of society? How can a revolution generate concrete proposals for change without falling back into narrow political discourse? These are questions that confront every uprising once the banners and batons are put away. Answering them requires what I call a “second-order revolution.”

Beginning in June 2013, many Brazilian cities erupted in a wave of street protests. They were triggered by an increase of seven per cent on bus fares, but turned into a more general statement of public dissatisfaction with the condition of the country: “we’ve had enough,” the public seemed to be saying.

Politicians struggled to understand and come to terms with what was happening, and tried in vain to identify representatives from the protestors with whom they could talk. After millions of people stayed on the streets for weeks, the bus fare increase was revoked, but many Brazilians continued their actions as other themes unfolded and more demands were made.

Many commentators and activists wrote about these experiences as a potential tipping point in Brazil, and tried to explain them in terms of the economic context of the country, lavish spending on the upcoming soccer World Cup, and the power of social networks to mobilize large-scale demonstrations.

Photos of the protests show millions of people on the streets, establishing a potentially-historic moment for the country. What’s interesting to me is that these images show a pattern common to street protests with most people facing in the same direction – marching in a straight line almost like a military division in action. But societies as a

whole don’t work this way (especially democratic ones), because people don’t agree on the details of how the established order should change after the protests have died down.

whole don’t work this way (especially democratic ones), because people don’t agree on the details of how the established order should change after the protests have died down.Protest is never enough to secure a long-term vision for a country, so the straight lines of demonstrations have to be re-shaped into new patterns of participatory democracy and dialogue. This is what is happening in Brazil.

Brazilians will continue to show their discontent about a country that is known for its corruption, and for the huge gaps that exist between rich and poor. But alongside the highly-visible public protests something more subtle is happening: conversations in public spaces about the concrete future direction of society.

These conversations represent a second-order revolution. They have the potential to transform the way in which social change is constructed by allowing new stories to emerge. And they invite citizens to take ownership of public spaces in order to explore competing narratives about the trajectory of their country and to fashion new collective understandings.

“Circles of dialogue” like these have taken place in many other places. In Israel, for example, more than thirty cities gathered around 1,000 tables in 2011 to explore the political and social issues that faced them. The main dialogue space (a plaza in Tel Aviv) was transformed into a huge ballroom with room for 5,000 people. Similarly, during the turmoil in Greece that took place from 2010 to 2012, the public occupied Syntagma Square in the center of Athens. Although the occupation didn’t produce much by the way of dialogue directly, it did open the way for other spaces and conversations to spring up.

In the case of Brazil, public conversations of this kind were organized in the four major cities, as well as in many smaller locations around the country. In the capital city of Brasília – one of the first to host these dialogues – the initiative emerged from a group of people who wanted to explore what it would take to create a bridge between the current situation and the futures they desired.

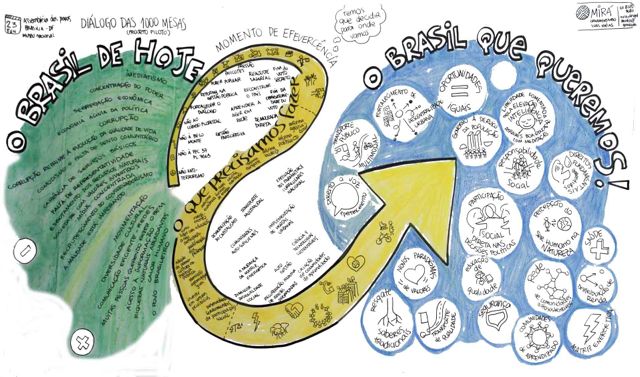

In a recent interview with me, Sérgio Monforte, who was involved in one of these circles, explained how the process started: “We were sitting in plenary in a public space close to the National Congress,” he said, “and realized that it would be a shallow conversation if we didn’t weave our ideas together.” Monforte and others proposed the setting up of smaller groups to explore questions without any pre-defined themes, and to come up with ideas for action. “Not everyone agreed,” he continued, “so at the beginning we ran a parallel group with the plenary.” Ideas were harvested to describe the transition between “the Brazil of today and the Brazil that we want in the future,” including “the death of oil” and building “networks of sustainable communities.”

These early discussions also produced a number of small, joint actions such as a video to explain how laws are created and changed in Brazil; an exercise to help people understand each-other’s views; and proposals on how other groups could be supported to host similar conversations. As a result of these proposals, a methodology guide was created based on experience from Tel Aviv. It uses a group conversation process called the World Café, a social technology that allows for conversations to take place at a much larger scale without squeezing out the diversity of different voices. At the end of the process, the results of the conversation are presented in visual form.

In São Paulo, dialogues took place along central Paulista Avenue, the financial hub of the country, but also in a public space that had largely been forgotten – inside the city’s legislative assembly. Ricardo Young, São Paulo’s city councilor, took part in that conversation and fed the results back into his work: “public dialogues are an essential instrument where the legislator can express his opinions and listen to different points of view about reality,” he told me, “by definition this is the space where a legislator should be.”

Will this process actually affect the future of Brazil as it continues to evolve? That’s the obvious question, and it isn’t possible to answer it right now. But without some form of large-scale public discussion it won’t be answered democratically. Václav Havel, the writer, activist and former President of the Czech Republic once observed that “I really do inhabit a system in which words are capable of shaking the entire structure of government, where words can prove mightier than ten military divisions.”

With no signs of the Communist regime collapsing and little hope on the horizon, Havel and his friends would meet secretly to host conversations and generate new stories about the future. They met in underground cafés and published alternative newspapers. They invited debate and created new ideas and interpretations about politics and economics. Even members of the Communist regime would sneak out to join these conversations. These small actions did not shake the larger system directly, but over time a different collective understanding about Czech society began to emerge.

Brazil today is very different to the Czechoslovakia of Václav Havel under Communism, but that doesn’t dilute the importance of the kinds of conversations he was referring to. Quite the opposite, since such conversations should be much more powerful in the public spaces of a democratic state. Over time, they could even open up an opportunity to transform democracy itself, from representative elections every four years to a continuous process of participatory public dialogue.

Street protests will not disappear (nor should they), but perhaps the demonstrations of the future will include a walk of millions, followed by thousands of dialogue circles. Perhaps the definition of new laws will be preceded by open conversations that take place in a public park near you, and hosted by anyone who is interested. Imagine what might happen if political representatives were to join these conversations to meet with their constituents face to face. No longer will political responsibility be delegated to the few. Instead, the public could take much closer ownership of the political process.

Complex societies require high levels of public participation, not just on the streets but in the spaces where ideas and opinions are born and shaped. These spaces could become laboratories of public engagement at a whole new level, opening the doors for a revolution in democracy.

Visit the Taking the Revolution Forward collection for more reflections on revolutionary movements.

Graphic above by Luiza Padoa and Juliherme Piffer: http://net.coolmeia.org/blog. All rights reserved. Photos courtesy of Augusto Cuginotti.

Manifesting a second order revolution in Brazil