-

What we know about each other matters. Especially when it comes to social innovation.

The most engaging and innovative social purpose organizations we have encountered in our work share at least one core practice. They are very good at surfacing the organization’s inner life – the actual, lived experiences that the people in the organization have as they interact with each other. We have been calling this practice inscaping. If social innovation is the art of fostering new and healthier ways of living together on this planet, then inscaping seems to be the raw material for such innovation.

It turns out, though, that inscaping is too broad a concept to explain some of the variation we see in the capacities of different organizations to become true social innovators. Many organizations might reasonably describe themselves as good at inscaping. They are relatively open and honest. The members of the organization care about each other and are willing and able to share their experiences, at least to some degree. Yet these organizations often struggle to fully develop their capacities for meaningful, resilient social change. Why?

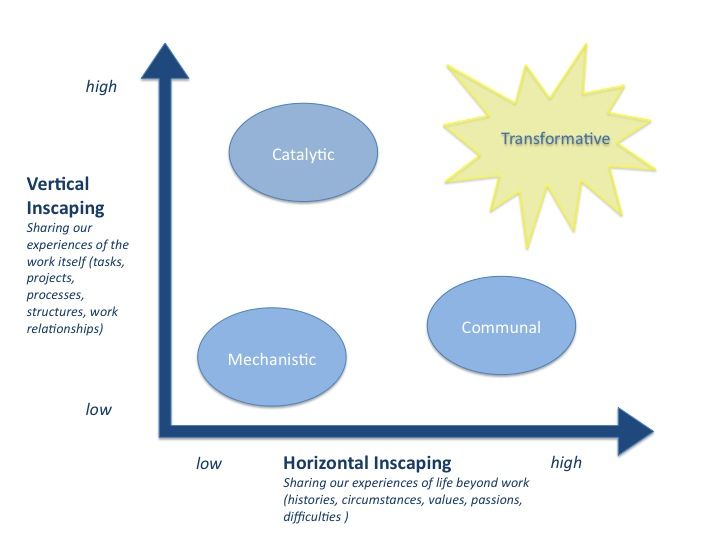

Inscaping seems to have two dimensions. We can think of these dimensions as ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’. Vertical and horizontal inscaping are interrelated, but they represent distinct kinds of interactions, and they have very different effects on organizational possibilities.

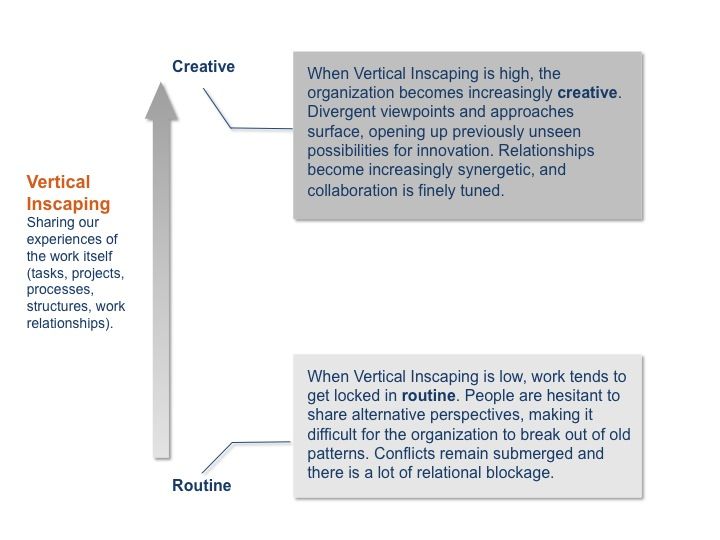

Vertical Inscaping

Vertical inscaping involves sharing our experiences of the actual organizational work we do. Our curiosities, passions, and fears about that work. Our ideas and intuitions. Our desires. Our struggles. And perhaps most importantly our relationships: How are we experiencing working with each other right now? What do we most appreciate about each other? What do we find most challenging?

Horizontal Inscaping

Horizontal inscaping involves sharing our experiences of life beyond work. Our broad hopes and values. Our current excitements and difficulties. Our histories. Our circumstances. Our worries. Our gratitudes. This kind of inscaping does not mean that we share every facet of our lives with each other. It simply means that such sharing is possible, that the vast areas of our lives that are usually out of bounds at work are no longer necessarily so.

Four Organizational Spaces

Why does the distinction between vertical and horizontal inscaping matter? In our experience, many organizations are good at one mode of inscaping but not the other. And this imbalance has a direct effect on the organization’s capacity for social innovation. This is easier to understand if we think about the ways that vertical and horizontal inscaping interact.

Mechanistic Organization

When both vertical and horizontal inscaping are low, work is routine and relationships are narrowly functional. While the organization may be perfectly competent at meeting predefined objectives, its capacity for learning and creativity will be limited, and it will have virtually no ability to move significantly beyond existing paradigms or to inspire such movement in others. People may be collegial, but the narrowness of relationships leaves overall human engagement low. People are unable to support each other’s personal growth and development. And there is little scope for reflecting on the organization’s impact in terms of its broader social context. The organization is essentially Mechanistic.

Communal Organization

When vertical inscaping is low but horizontal inscaping is high, there may be a strong general sense of connectedness and mutual support, but because people are hesitant to speak honestly about their immediate experiences of working with each other, organizational creativity is weakened and the organization may feel stuck.

Conflicting ideas, temperaments, paradigms, goals, and emotions are often submerged, resulting in blocks that constrain healthy collaboration and that leach energy out of the organization via gossip, politicking, and misalignment between personal passions/skills/interests and organizational structures. The organizational conversation will naturally include broad exploration of values and meanings, but people may find it difficult to translate those values and meanings into concrete, innovative projects.

In our experience, many social purpose organizations tend in this “communal” direction. They are open to and appreciative of the whole human beings who make them up. Organization members may support each other’s growth with a great deal of interest and compassion. But at the same time, Communal organizations often cling to a kind of surface-level peacefulness and politeness, which leaves them reluctant to explore the actual, messy experiences people are having as they pursue their work.

Communal organizations avoid work conflict. They avoid uncomfortable or politically incorrect perspectives. And while Communal organizations are deeply connected in a general way to broad social values, they can get locked into the superficial words and structures that currently represent these values rather than digging into the values experientially. The focus on established words and structures makes it difficult to experiment with how values might be enacted in new, imaginative ways.

Catalytic Organization

On the opposite pole from Communal organizations we find Catalytic organizations – organizations that have high vertical inscaping but low horizontal inscaping.

Catalytic organizations are unafraid to open up the conversation to include divergent ideas and intuitions. In the name of experimentation, people are encouraged to articulate their own peculiar, iconoclastic approaches to the problems the organization is wrestling with. And conflict is seen as the raw material for new knowledge creation rather than as something that threatens the organization. Consequently people are able to connect themselves to their work and to collaborate with each other in nuanced, well-honed ways.

However, the experiential sharing in Catalytic organizations is largely limited to experiences directly linked to the work itself. People may interact with each other in richer ways than they would in role-bound, Mechanistic organizations. But such interaction is still mainly instrumental – rooted in what you are good for rather than who you are.

Our broader life experiences have little meaning in this context. We may value each other’s skills and personalities but know little about each other’s personhood. So our relationships, while energizing and fruitful, are thin. And there is limited space for us to consider social and moral values that extend beyond organizational boundaries.

Many high performing businesses are largely Catalytic. They draw on the variegated work experiences of their members to consistently create novel products and programs. But because the organization’s explicit objectives are taken as the ultimate markers of context, innovation is rarely interrogated against deeper values and broader social issues.

Catalytic organizations can be thrillingly creative, but to what end? They are great at the ‘what’ and ‘how’ but not at the ‘why’. They come up with imaginative new products and programs but have trouble transcending the deeper social patterns that underly our most intractable social problems. The key to broaching these patterns is to let the life experiences of the people in and around the organization begin to inform our work.

Nonprofit organizations can find themselves bound up in a Catalytic space as well. Their immediate objectives (clients served, laws changed, money raised, etc.) become their sole reality. Everyone and everything is seen through the lens of those objectives. The organization will have trouble reconsidering and recombining those objectives, and new possibilities for even deeper social change will be overlooked.

Transformative Organization

Organizations with a high degree of both vertical and horizontal inscaping have the best potential as social innovators.

Here, the vibrant, imaginative sharing of work experiences combines with the compassionate, meaningful sharing of life experiences to move us beyond mere surface rearrangements of our existing paradigms.

Social innovation has two facets. The “social” – which requires us to explore questions of ultimate meaning not as roles but as humans; horizontal inscaping can help us do this. And the “innovative” – which requires us to explore and understand the gifts, inspired urges, and temperamental idiosyncrasies of the friends with whom we collaborate as we move through the daily challenge of trying to create something together; vertical inscaping can help us do that.

Working in this way is hard for us at first. It takes practice. But it’s worth it. The organizations we know that are the best inscapers are also the most engaging and imaginative places we have come across. They are loving. They are fun. And they crack open and refashion some of our most stubborn institutional patterns with a simplicity and grace that has to be experienced to be believed.

[Note: we will be posting some more concrete examples of inscaping practices in the near future.]

*Photo on front page by Tim Caynes

The social innovation space