-

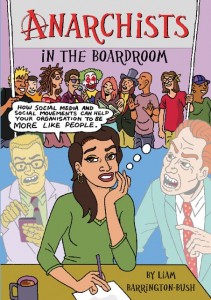

We are stoked to introduce you to another new contributor to Organization Unbound Liam Barrington-Bush, author of the book Anarchists in the Boardroom: How social media and social movements can help your organisation to be more like people. If you happen to be reading this from London, there might still be tickets to his book launch on September 25th. The reflection below represents a sneak preview…

Children’s social services in England, like those of many other countries, don’t always have a sparkling public reputation when it comes to face-to-face relations. Like police, social workers who tackle state-mandated child protection cases spend their days witnessing and intervening in many of society’s darkest moments. From paedophilia to domestic violence, a social worker often observes the worst of what human beings are capable of in a typical working day. It takes a special kind of person to avoid becoming jaded by a constant barrage of such experiences.

Combine those experiences with cumulative decades of government policies legislating ever-more-extensive reporting requirements in the name of ‘greater accountability,’ to the point where frontline staff are expected to spend, on average, 60 percent of their working week filling out paperwork. For instance, when a child on your caseload goes missing, you may not be able to escalate the investigation until you have received proper sign-off on a range of time-consuming process documents. Without these documents, you, personally, could be found liable for whatever becomes of the missing kid. Sometimes these processes are hardwired into computer systems and cannot be easily overridden, meaning that reporting undermines the ability to, say, involve the appropriate specialist, or a parallel agency, on short notice, in the critical moments when a child’s safety is at risk.

Indeed, the professional accountability systems of child protection agencies in the UK (and elsewhere) often undermine the work of those who are meant to be ensuring child protection.

When someone who understands complex systems sees that something is not working as intended, they will aim to shift the relationship dynamics, rather than the people themselves. In practice, this might mean starting to better understand the relationship dynamics among individual social workers; among social workers and senior practitioners, doctors, lawyers, probation officers, etc.

When someone who understands complex systems sees that something is not working as intended, they will aim to shift the relationship dynamics, rather than the people themselves. In practice, this might mean starting to better understand the relationship dynamics among individual social workers; among social workers and senior practitioners, doctors, lawyers, probation officers, etc.From there, working to improve these relationships becomes key, but doing so inevitably involves acknowledging that power and hierarchy distort the sharing and flow of information. In the investigations that have followed several high-profile child welfare scandals, poor relationships among professionals have been identified as a central factor in the gaps that appeared, yet have remained largely unaddressed, as the application of their conclusions would challenge the underpinning mythology of compliance-based accountability.

As the number of oversight policies grows, they often start to work against their stated aims, running afoul of one another as they cross paths in the real world in ways their architects hadn’t planned for. The social worker, so preoccupied with the paperwork their job requires of them, misses a more obvious problem in a child’s home because their attention was absorbed by their clipboard, or the stresses of another case for which they haven’t been able to receive the necessary support. These are the kinds of policies that gradually produce an inability to see the forest for the trees; the ‘abuse’ from the ‘three-page list of signs of abuse.’

An engineer would describe these policies as new ‘failure modes’: solutions to particular problems that unexpectedly create new problems in their wake. But engineering isn’t the only place where proposed solutions have unintended consequences. For example, a classic ‘failure mode’ in urban planning might emerge when a traffic light is installed at a local intersection following a car accident there. Seems sensible, right? Then at another intersection a few blocks away, another is installed following a separate accident. And then again, in the same vicinity, after a third tragic crash…

Eventually, the lights are so numerous, that frustrated motorists and pedestrians either start running reds or jaywalking out of frustration at their inability to get around, or stop paying as much attention because the traffic lights have let them absolve their sense of personal responsibility for road safety. In both cases, the result is the same: accidents once again begin to rise.

Alternatively, Bohmte, Germany, and Drachten, Holland, removed all traffic regulation, forcing motorists to pay closer attention to what they are doing behind the wheel. This system is called ‘Shared Space’ and was envisaged by the late Dutch traffic specialist Hans Monderman. The European Union has since part- funded its continued implementation around the continent, as it has proven so successful in reducing accidents and improving traffic flow in several sizable cities. When everyone is paying attention and knows they are responsible to each other for their choices on the road or sidewalk, everyone benefits. This is trust- based, mutual accountability in action.

No method of compliance can effectively replace the kind of accountability that mutual trust provides in a relationship. The work created in attempts to do so is immense. Numbers have traditionally been seen as a substitute for trust, providing a way of measuring whether someone has done what they said they would. Or so we tell ourselves.

Too often we see numbers as an end point – the holy grail of research, evaluation, analysis, planning – rather than a step along the journey towards better understanding. But, as Margaret Wheatley says so unequivocally, ‘nothing alive, in all its rich complexity, can be understood using only numbers. Nothing.’

When numbers become the end game, the pressure to manipulate their journey, fiddling, adjusting and otherwise reconfiguring them is immense. This is the essence of Goodhart’s Law, named for Charles Goodhart, a former director of the Bank of England. Goodhart’s Law declares that if numbers are used to control people (as with any numeric report requirements, as well as bonuses or penalties based on achieving or avoiding certain figures or numeric standards), they will not create the intended results. They may even undermine them.

. . .

In Croydon, officially the southernmost Borough of London, a forward-thinking local council Chief Executive broke long- established tradition in 2007, recognising the very real human consequences of what he called ‘the cult of professionalism’ on the Council’s social services. By helping reconnect managers with the human experiences at the other end of their policies, Jon Rouse found the approach of those same managers changed significantly, as policy making became less of a bureaucratic, and more of an empathic, experience.

When I had a chance to ask him about the cult of professionalism, Jon Rouse described it as ‘a tendency for professional institutes to use professional training to embed a set of norms, a way of doing things that makes it more difficult than it should be thereafter to inculcate cross-professional working and shared accountability to the service user.’ More colloquially, the behaviours of the cult make it harder for people in professional roles to connect and communicate with one another, inside and outside of their organisations, creating a range of problems for those they work with. Accountability to the public is their most serious cost.

Rouse, unlike many of his counterparts in local government, was unwilling to concede that families who felt they had been torn apart by ill-conceived social service provision were simply an inevitable cost of his particular line of work. Rather than ordering a review of local children’s services, or sacking a director and allowing the cult to continue its rituals, Rouse trusted a hunch and went straight to what he felt was the core of the issue: the professional environment that had been gradually built up over decades in the council had buried the sense of empathy of those at the top of the social services command chain.

Following this hunch, Rouse involved staff in a process called ‘emotional moment mapping,’ ‘where you actually follow the customer’s experience of using your services in terms of the emotions that are evoked by the experience.’ The results helped to rekindle a largely dormant sense of empathy between senior staff and service users, highlighting the human experiences of those who were receiving a range of social services from the council.

Following the mapping exercise, Rouse arranged for several of his senior staff in the Council’s social services department to see video testimonials from some of the local people who felt wronged by social services in the borough. Before doing so, he made clear to his colleagues: ‘your role is not to defend the Council’s actions, it is simply to listen and to hear. ‘Specifically, Rouse recounts, ‘this was not to make them feel bad about themselves or each other but as a motivation to improve the design of those services and therefore the future experience.’

When I asked why he hadn’t encouraged face-to-face meetings, instead arranging private video viewings, he said, ‘It needed to be a private experience in order to allow the staff members the freedom to have a natural emotional response.’ When the sessions took place, several Council staff, often decades into their careers in local government, were profoundly affected. Some were brought to tears by the stories they heard. People hardened by years of the cool, professional disconnect that came from being told they were ‘the experts’ on child protection were deeply shaken by the experience. The human stories, unmediated by the broken telephone of hierarchical communication, cut through the usual justifications that had allowed them to maintain their distance from the frontlines.

Andrea Smith is a community organizer in Brooklyn, New York, working against the growing tide of professionalisation and its corresponding emotional disconnect between staff and service users of domestic violence organisations. ‘While some boundaries are healthy,’ Smith writes, ‘the particular kind of distancing within anti-violence organizations is counterproductive to any goal of creating connection.’ She goes on, ‘Eliminating this difference increases the potential… to allow survivors to create the kind of relationship they want between themselves and the organization.’

While the work of a Council Chief Executive and a grassroots domestic violence activist in certain ways couldn’t be more different, they have both seen the pitfalls of the emotional distance created by moves to professionalise their work on either side of the Atlantic. The disconnected professionalism that is increasingly taught in so many social work programs reduces the space for individual judgment, and stronger relationships, turning a role that traditionally relied on a range of highly developed interpersonal and subjective decision-making skills into an increasingly administrative function. And the increased distance of senior management from the issues has the tendency to reinforce the logic of this professional objectivity.

Shortly before his death (from non-traffic-related causes) in 2008, Hans Monderman, the inventor of the ‘Shared Space’ method of urban traffic regulation, opined that the reason for his approach’s success was that it encouraged basic interaction between drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists.

Shared Space works, Monderman said, because it forced everyone ‘to look each other in the eye, to judge body language and learn to take responsibility — to function as normal human beings.’

With his mapping exercise and his video testimonies, Rouse forced some of his staff into an uncomfortable place – ‘unprofessional’ as it was – but in doing so, did for his senior managers what Hans Monderman’s traffic system has done for so many European urbanites. He helped them ‘to function as normal human beings,’ reigniting some of the empathy that years in the system had buried.

‘In the next three to four months,’ he observed, ‘there was a definite loosening up of some of the professional boundaries,’ Rouse told me. While admittedly, some of the old tendencies began to creep back into working habits, ‘we were able… to use the window to start the process of change in our early intervention and family support services, and we now have a much improved service as a result.

By helping a small group of senior staff to reconnect with a dormant sense of empathy, Rouse opened the doors to critical learning from previously ignored places. This kick-started a process that actively included the perspectives of those most affected in the development of social care and service policies across the borough, making those services more responsive to the people receiving them.

Missing the forest for the trees

One Response and Counting...

Another great(!!) article.