-

Many people involved in social purpose work champion the idea that organizations need to become places where we can relate to each other not just as roles but as whole human beings. We believe that when we are free to express dimensions of ourselves that don’t fit neatly into job descriptions, our work becomes more engaging and our relationships more authentic.

Many people involved in social purpose work champion the idea that organizations need to become places where we can relate to each other not just as roles but as whole human beings. We believe that when we are free to express dimensions of ourselves that don’t fit neatly into job descriptions, our work becomes more engaging and our relationships more authentic.

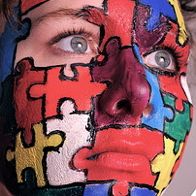

I think this is true. But what is less well understood is that treating each other as the patchwork, unruly human beings we are, rather than the zippered office functionaries we pretend to be, is also the only way we can really come to understand, let alone affect, the larger institutional patterns we are trying to change.

Why? Suppose we are interested in food security. We decide to create an innovative project that will help transform the causes and effects of institutionalized food systems. Our project will include a food bank, a buying cooperative, training in sustainable urban gardening and food preservation, health workshops, policy review and advocacy work, etc.

So far so good. But if we really think about the institutional patterns that are bound up in all of the issues related to food security, we are just getting started. A complex theme like food security is woven from an almost endless series of institutional threads: economic paradigms, cultural beliefs, law, class, health, race, gender, education, religion, crime, addiction, socio-environmental interactions . . .

And this complexity would be true of any social issue we decide to address. Institutions are sedimented. They are layered one atop the other with such density and pressure it is almost impossible to analytically unpack them. Systems theorists are right when they say we can only understand complex systems by looking at the whole. But how do we do this?

One of the most powerful ways we can develop a holistic point of view is by moving beyond “systems thinking” to “whole-person-experiencing.” Every person we encounter is a powerful nexus of institutional forces.

Do you want to understand the interrelationships between health and law and gender and race, say? More importantly do you want to be able to work effectively with those interrelationships and shift the forces behind them? Then spend some meaningful time with your neighbor at work, because you will find all of those forces right there, merged into a functional and coherent, if often troublesome whole.

I carry countless deeply embedded social patterns inside of me. So do you. So does the client coming to eat at the food bank. So does the volunteer. So does the funder. And these patterns play out in our daily interactions in mysterious but tangible ways. Every moment of authentic interaction we have with another human being is a doorway. We can begin to understand what it is we are trying to change and how we might change it not through abstract models, but through lived experiences. I’m not saying system models aren’t helpful, just that they aren’t enough.

I think of Dr. Paul Farmer and his relentless need to really know his patients. Spending a perfectly absurd proportion of his time walking and visiting in rural Haiti, Farmer has helped transform the way we think about and act to treat communicable diseases in poor communities.

I think of Inter Pares, the social justice organization in Canada that Tana recently wrote about. The people at Inter Pares have spent 30 years trying to discover what it means to live feminist values in their daily organizational practice. They do this not by relying on philosophies or structures (though these are important to them) but ultimately by relating to each other, making space for and wrestling with all the various and complicated ways that they have navigated their own journeys through gender, culture, and power.

Farmer and Inter Pares have helped to generate meaningful institutional change on a scale that breaches international borders. But they have done this by grounding themselves in the fullness of even the most glancing relationships with their fellow travelers.

I believe that deep institutional transformations happen largely through a stream of small awakenings – epiphanies so shy we barely notice them in ourselves let alone in others. Until, that is, what was once only an awkward or tender or painful or amusing encounter with the strangeness of another human being coalesces into a resilient new pattern of hope.

Whole person, whole system

One Response and Counting...

This is timeless. It makes systemic change or whatever change we are trying to be in the world less daunting. It amplifies the value of seemingly ordinary interactions with people within and outside our regular circle…

One of the crazy ideas bubbling up at Zenith Cleaners is to get people trying to bring a “solution” or “product” to a new “market” to go spend time with everyday people in that environment and one of the ways to connect with people deeply is to clean for or with them as part of spending “meaningful time” with them. When done whole person to whole person, magic can happen.

Institutions are not abstract concepts on paper but deeply held beliefs, paradigms and thinking patterns in individuals. It ties with our idea of cleaning the intangible. The intangible is held within individuals and we can only “see”, “touch” and “handle” it by having meaningful whole person to whole person interactions. The beauty of whole person to whole person interaction is that either party runs the risk of being transformed, seeing better, having clearer windows.